|

In John Green’s The Anthropocene Reviewed, Green reviews things from Teddy Bears to the song “Auld Lang Syne”. And I find it fitting that now, I am reviewing a book that contains only a life catalogued in a five-star system. When asked what the book is about, Green mentions that he’s never quite sure, that maybe it’s about growing up, maybe about the effect of time, and maybe as broad reaching as about the human condition. And to that end, it does mean all those things to him, and most likely more.

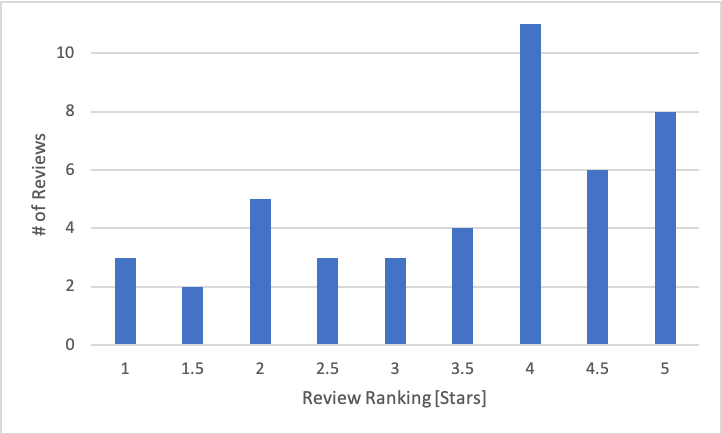

My personal favorite essay, as I’m sure with the other 100,000 people who have watched the video essay on Youtube, is that of “Auld Lang Syne”. There is an honest earnestness in the way Green weaves his own life experiences with the convoluted and sometimes melancholy history of the song. And I’ve noticed, as mentioned in the bits of his introduction, that without the personal flourishes of each review, they would feel detached and nearly sterile. Because of this, the reviews that have strong personal connections are the essays that stand out. Though, there are moments where it seems Green only has a loose personal connection to the topic, and thus the narrative relies on history rather than a deeply intricate understanding of him, as an individual. And while I understand that yes, it is a book of reviews, so what else is it supposed to be about other than the exact thing being reviewed. Though, the detached essay of “Yips” contrasts so heavily with the essay following it “Auld Lang Syne” that I feel as though its significance is nearly lost. I’ve learned that the reviews say more about the reviewer than the things they are reviewing. Such as: what things does the person value, or what things did they not include, or how is the thing personally relevant. Final Rating: 4/5 (As a side note, there are 44 reviews (45 if you include the half-title page review) with three 1 star, two 1 ½ stars, five 2 stars, three 2 ½ stars, three 3 stars, four 3 ½ stars, eleven 4 stars, six 4 ½ stars, and eight 5 stars. This is plotted below.)

0 Comments

There are only a few books in my life that I can say have impacted me to a great extent, and Night by Elie Wiesel is one of them. Simply put, he forces the reader to confront a battered history that had befallen the Jewish people in Europe during World War II. I can only say that it has brought me a greater understanding of the horrible actions that were taken in this shameful era of human history. But to greater extent, it puts a personal and vulnerable touch to what the Holocaust was. When I was younger, I had learned about the Holocaust with an almost separation from the events. I knew that 6 million Jews had been murdered by Hitler, but on that grand of a scale, I couldn’t truly comprehend each of those lives in all their complexities and tragedies. I have found myself digging for information on tragedies such as the Holocaust as it shows the raw and unfiltered humanness of life, oppression, emotion, and death. We rarely like to bring up things so painful that a word seventy-five years later still causes hushed whispers. But as time moves its metal hands, we can only spend that time understanding and progressing from what we had been before. Night is that much needed reminder of the atrocities that humans have the ability to do to each other. I would like to reflect on a passage Elie Wiesel’s acceptance speech of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. “…I have tried to keep memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices…And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim… Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must-at that moment-become the center of the universe"(Elie Wiesel, 1986). I wish that things like this never happened, but seeing as we cannot alter history, we can only hope to prevent anything tragic in the future. We can only force ourselves never to forget, to inform our children of how horrible actions had caused endless suffering. And to never deny these concrete facts. To learn and read from survivors like Elie Wiesel gives us invaluable insight and personal accounts of a history that should never be repeated. I continuously am filled with a simple yet pressing question that doesn’t seem to be answered, which is: How could humans do this to one another? How could so much baseless hatred be directed towards a certain type of people? It brings me great sadness to have to reflect on something that should have never happened. And so, as Elie, I will advocate, stand up, and do everything in my ability to stop the suffering that befalls individuals and groups of people. Because if we don’t help one another, then it will only perpetuate more suffering that the world shouldn’t endure.

Final Rating: 4.5/5 When the Emperor was Divine by Julie Otsuka is a historical fiction novel that follows a Japanese-American family during World War 2 as they are displaced from their home in Berkley, CA to an internment camp in Topaz, Utah. There are three distinct stages that the novel follows: travel to Topaz, life at the internment camp, and the reverberating effect afterward.

The novel begins by following the mother, keeping the story grounded and practical as she must deal with the logistical problems of being uprooted. These activities range from burning items that tie them to Japan, packing or discarding their stuff, and killing their dog. Otsuka provides the characters distance from their own actions by supplying the narrative in third person while keeping the family members nameless. In effect, Otsuka is implying that it could be anyone that takes the place of these characters. Though that doesn’t mean that the characters are dimensionless. The son at first pass has an optimistic attitude towards the whole ordeal, but Otsuka may have used this as a thin veil to describe his obliviousness. This is because the son is young, while his sister is old enough to understand what is going on. She is more reactionary, which the mother interprets as rebellion throughout the train ride and their subsequent life in the camp. Otsuka’s characters are painfully asked to wait: at an old horse race track, on a train to Topaz, at Topaz for the war to end, and for their father to come back. It is in these moments of waiting where Otsuka fleshes out the characters into whole beings with hope of their return, anxiety of the state of their home, and contempt for their living state. Otsuka forces the reader to realize how the immediate pause—or in some cases total destruction—of American lives should not have been justified by the government. But even so, these characters and those actually interned at the camps had to find a way to continue living. The mother in one scene after trying to be the stable foundation for her children breaks down by refusing to eat. While the sister separates herself from the family by being with other friends in the camp, and the son tries to act as the stable earth. When the family is allowed to go back home, the experience then switches to the point of view of the son. And in this way, it reaffirms the idea that the characters tried to separate and distance themselves from their own experiences. The backbone of the novel is the relationship between the family and the father. Otsuka provides flashbacks, letters, and stories of the father to build this idea of a strong, loving, and caring person. And throughout most of the novel, the father is experienced indirectly through memories of a rosier time. And without that hope to meet again, the characters would’ve broken down with no motivation to continue. Otsuka builds the father as one thing, but once reunited, the reader experiences the massive disconnect between reality and the idea of the father. This disconnect is also felt through the rejection of their friends, neighbors, and society as a whole when the mother tries getting a job. The novel finishes with the payoff that Otsuka builds up to. The father, who had been taken in by the US government to be questioned about his allegiance and suspected of being a spy, is the focus of the final chapter. In the point of view of the father, who is innocent of all accusations, instead admits responsibility of the accused actions. And while the reader knows that he has done nothing of what he admits, the father’s willingness to take the fault shows his deep loyalty to America. It is a noble act to say sorry for something that one has never done, and Otsuka knows that making this the final sticking point makes an explicit comparison to the actions of the US government. Final Rating: 4/5 |

AuthorMaxwell Suzuki is a writer, poet, and photographer based in Los Angeles. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed